When TL became the French Republic’s military governor of San Domingue, he sent both Placide and Isaac to be educated in France. As a consequence, TL became the unacknowledged leader behind the first slave rebellions in the northern district of Le Cap in early 1791. The new administration reshuffled slaves among the plantations and increased demands on muleteers like TL who kept horse-driven sugar mills going. In 1789, his friend Bayon was sacked as administrator of the Breda states due to corruption and mismanagement. Suzanne brought to the relationship a mulatto son, Placide, whom TL loved more than his black son with Suzanne, Isaac. TL “married” again a laundress in Haut du Cap, the slave Suzanne.

His daughter inherited Dessir’s surviving slaves, including Dessalines. In the 1780s, TL lost two of his sons with Cecile. By then his first wife Cecile had ran away with the free mulatto and wealthy slave owner Guillaume Provoyeur.

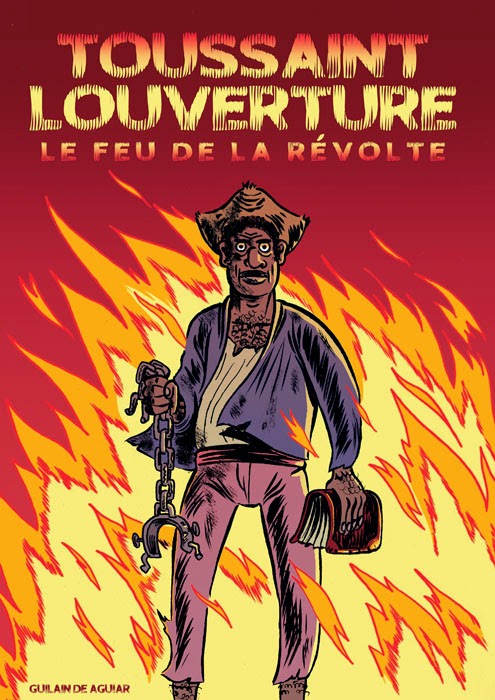

In 1782, the bankrupted TL returned to the Bréda plantation to work for Bayon as a muleteer. TL mismanaged the plantation and two of the slaves he “rented” died. In 1779, TL moved out of Haut-du Cap to run the coffee plantation of his white son-in-law, Dessir, with 13 slaves, one of whom happened to be Jean-Jacques Dessalines. In 1776, Bayon granted TL manumission in very obscure circumstances. It was found sown into the frock TL wore in prison, along with a collection of other notarized papers. He wrote and rewrote the petition several times, forcefully claiming to be primarily a Frenchman, a Black general of the Republic. During his 1803 imprisonment near the Swiss Alps, TL left a 16,000 word petition to Napoleon in phonetic spelling in his own handwriting. TL was an autodidact who at age 50 began to teach himself reading and writing. De Bréda mutated into “the doorway” by sheer self-will. In the 1790s, as he helped organize the slave armies to destroy plantations around Le Cap, Toussaint understood his role in providential Catholic terms -he had become “a doorway or the opening,” L’ouverture, for slaves to gain both emancipation and French civilization, including literacy and classical learning. Eventually, Toussaint developed a close relationship with Catholic priests and came to reject “African barbarism and superstitions” throughout his life. On Nov 1, 1742, the child was therefore christened “Tous-saint de Breda.” Toussaint grew up among slaves speaking Fon and practicing Vodun. The child was born on the Day of all Saints to an Allada aristocrat named Hippolyte and an Aja woman named Pauliine, both slaves at Haut-du Cap, one of four plantations owned by Pantaleón de Bréda, an absentee owner.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)